As new coronavirus cases spike in the U.S.—Florida alone now has 12 times more cases than the entire country of Australia—healthcare workers still face a shortage of N95 masks. Many hospitals are now reusing the masks, even though they’re intended to be thrown out after a single use. Various solutions for disinfecting masks or increasing the supply are in the works, but a new silicone mask now in development is designed to be used and sterilized repeatedly, and could be as effective as the gold standard of an N95 respirator.

Development of Reusable Silicone Mask to Address N95 Shortage

“When the virus started popping up in the U.S., we talked about the need for PPE, and identified really early on that there was going to be a large deficit within the United States as well as the world,” says James Byrne, a radiation oncologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and research affiliate at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research who is part of a multidisciplinary team developing the new mask. “We really put our heads together to try to come up with something that was sustainable, and that’s how we really came up with this reusable, scalable, conformable, flexible mask.”

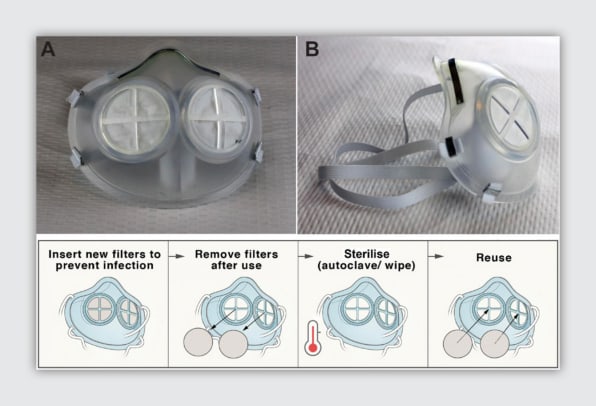

The team chose to use silicone rubber for the main part of the mask in part because of its durability—it’s the same material used in some baking equipment, and can easily withstand high temperatures. In a study of a prototype of the new mask, the researchers tested sterilizing it in an oven. They also tested a steam sterilization device and by using bleach or rubbing alcohol. Nothing damaged the material. Because it can be sterilized in several different ways, it can be used anywhere. “We wanted to have a system that could be accessible and used by anyone globally,” says Giovanni Traverso, an MIT assistant professor of mechanical engineering and a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, another member of the team.

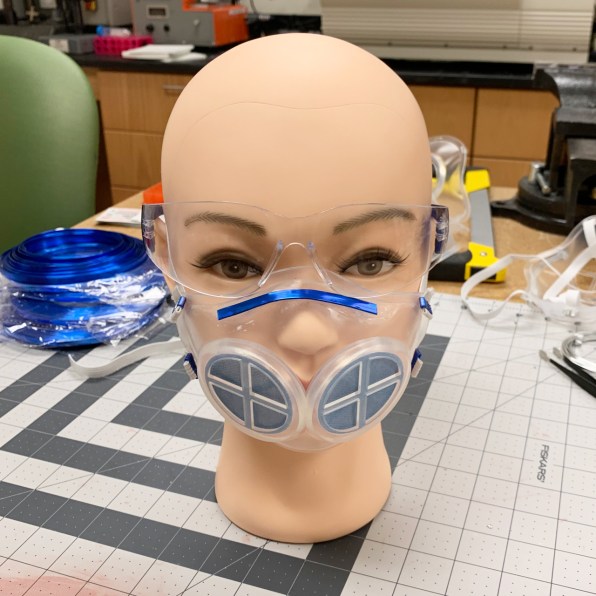

It’s also possible to quickly make huge volumes of silicone masks. “Having something that was scalable, meaning that we could relatively quickly make many to support a large population was critical,” Traverso says. “Injection molding of silicone is something that is recognized in the industry.” The material, which is already used in some anesthesia masks, is also comfortable and flexes to fit different faces; in a small test of a prototype with healthcare workers, around a quarter said that they preferred wearing it rather than a standard N95 mask. Because the material is clear, it can also make it easier to communicate with patients.

Two breathing holes in the mask use small N95 filters that can be popped in and thrown out after each use. By using far less material, it should be possible to meet demand more quickly. It also reduces waste. But the researchers are also exploring the use of a different filter material that could be sterilized and reused.

In tests with 20 healthcare workers, the team found that the mask could fit each individual correctly. They’re slightly tweaking the design based on feedback from the tests; one change involves slightly shifting the position of the filters so that it’s easier for patients to see the expression of the healthcare worker.

The researchers are now also setting up a company to bring the masks to market, as they run the prototypes through the final tests that will be necessary to get FDA approval. They’re also beginning talks with the FDA about emergency use authorization, both for healthcare workers and the general public. For hospitals, the switch to reusable masks could save money. The team is currently running both an environmental impact study and a cost-effectiveness study, and has estimated that its mask could cost just $15 and be used up to 100 times, making the cost per use likely less than a quarter, with the filter inserts less than a dollar. “There is a potential significant savings compared to the standard disposable system,” Traverso says.